Coral reefs are doing it tough. Around the world, most coral reefs are in decline. The most serious current threat is warming oceans caused by climate change. Marine heatwaves have caused widespread coral bleaching and death.

Reducing carbon emissions to help our climate get back on track is the single most important recovery action for coral reefs. However, while threats are still active, restoration interventions can help keep coral cover on local reefs.

At Reef Recruits, we work to get corals back on to damaged reefs through direct larval delivery. In short, this means we collect coral spawn during annual mass spawning events, we contain the developing coral embryos until they become competent larvae, then we transfer these larvae to the ocean floor at a damaged reef where they settle directly onto the reef. Through natural processes, only a small percentage of baby corals survive the first 6 months, but after that survival rates are high and after a few years of growth, improvements in coral cover are clearly visible.

In more detail…

Coral spawning

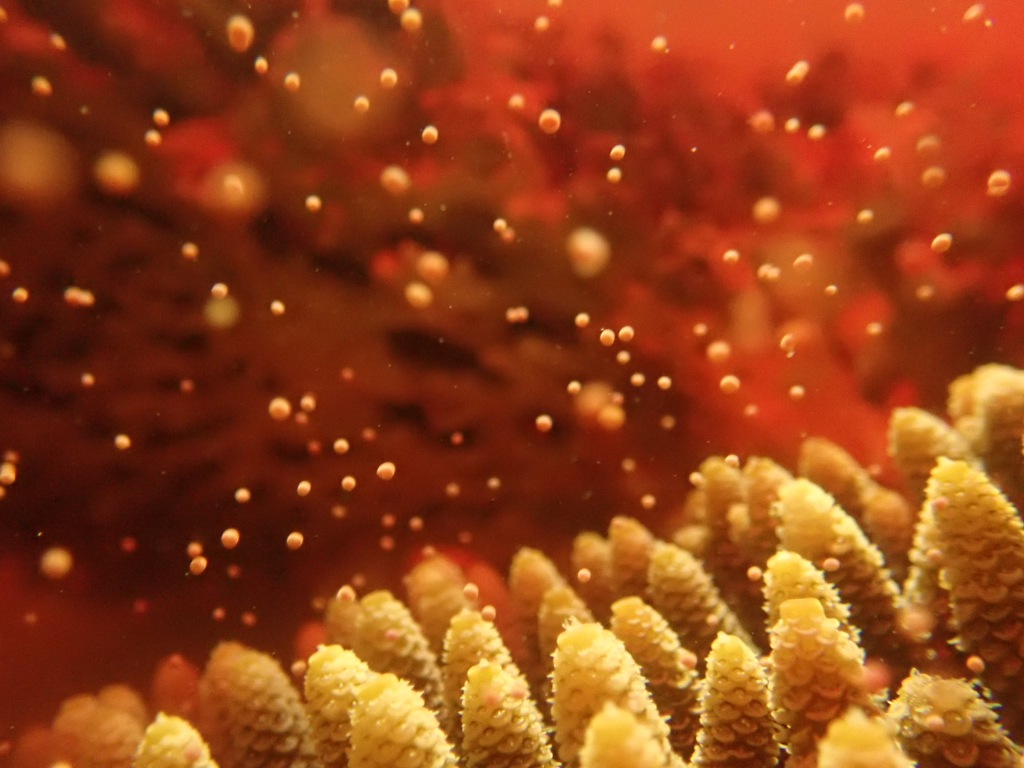

Many species of coral reproduce through synchronised mass broadcast spawning. Corals of the same species release bundles of eggs and sperm at the same time on the same night of year, so that when these bundles float to the surface there is a good chance of meeting a suitable partner from the same species. Each species has its own preferred time and night, usually a few nights after the full moon in late spring/early summer. So there isn’t one special night when all corals spawn, there’s a spawning season which is generally a few nights across 2-3 lunar cycles when mass spawning might occur across a healthy reef system.

With our Tropwater JCU partners, we use custom-designed spawn catchers to safely capture millions of spawn bundles. On spawning nights, we position these floating pontoons with suspended nets in a reef channel where the tidal flow is likely to carry the floating spawn bundles. Once spawning is well underway and the catcher has enough spawn in it, we close the net at the back and move the anchor point to the bow, converting the catcher into a larval rearer.

Larval development

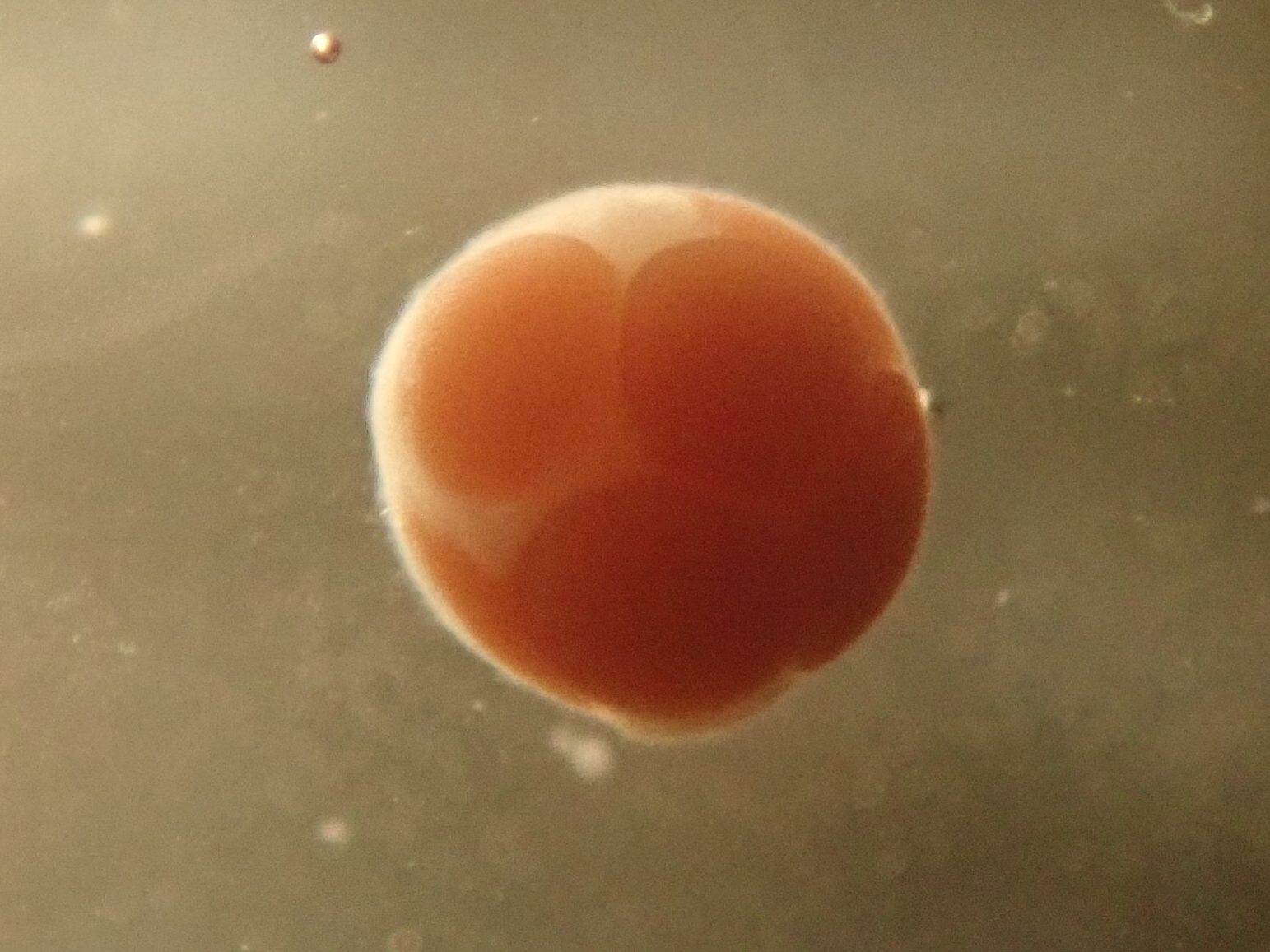

Coral spawn bundles break apart when they reach the surface, so that the eggs and sperm can mix and find appropriate partners from the same species but a different parent colony. Once an egg has been fertilised, an embryo starts to form and goes through several distinct development stages on its way to becoming a coral larva.

These photos are from collected subsamples, but most of our embryos are left to develop in the ocean, contained safely inside our larval rearers. It takes around a week for larvae to mature to become ‘competent’, which means they are ready to find a place to settle on the reef and metamorphose into coral polyps. During that week of rearing, we monitor the developing larvae closely and carefully clean the nets each day to maintain good water quality.

Net cleaning and microscope photos: Nicole McLaughlin

More information on the rest of the process coming soon.

You can read more about direct larval delivery in these scientific articles:

Increased coral larval supply enhances recruitment for coral and fish habitat restoration (2021). Peter L. Harrison, Dexter W. dela Cruz, Kerry A. Cameron and Patrick C. Cabaitan, Frontiers in Marine Science.

Density of coral larvae can influence settlement, post-settlement colony abundance and coral cover in larval restoration (2020). Kerry A. Cameron and Peter L. Harrison, Scientific Reports.

Enhanced larval supply and recruitment can replenish reef corals on degraded reefs (2017). Dexter W. dela Cruz and Peter L. Harrison, Scientific Reports.